Perfect Storms

and the Butterfly Effect

So far, this autumn has been stormy. The typhoons in Hong Kong a few weeks ago blew our friends’ plans off course. Lilian and her family were en route from Australia, but the weather grounded the plans and they couldn’t make it to London. As a result, our other friend Elen cancelled her plans for her 40th birthday drinks on the Friday night, and the picnic we’d planned for the Sunday with all our university friends was relocated to South London and rescheduled for the following week - which was fortunate in the end, as another of our friends, Alpa, flew in from Washington at short notice and so we got to see her too.

By the next Sunday, Lilian had reached London, but so had Storm Amy. The wind flung fallen leaves in a barrage across our gathering, blanketing our picnic mats from one direction and then the other. We had to raise our voices to be heard over its howls. At one point a two-metre long branch fell from one of the tall trees and landed a few metres away; it was verdant with leaves and so springy that the boys took turns jumping on its curved arc it like a one-dimensional trampoline. Meanwhile, I received a text saying the Royal Parks had all been closed.

But it wasn’t raining, and we had so much to catch up on, and nowhere else to go, and so we stayed. It’s twenty years since we all met at university, and these days it’s rare that we can all converge in the same place and same time. But here we all were, except Tom and Miranda and their family, who couldn’t make the rescheduled picnic. We had been fortunate to see them a few months ago for a day in Brockwell Park to celebrate Miranda’s fortieth, with a lavish picnic, session in the splash pad and rides on the miniature locomotive. We brought a structurally unsound mushroom quiche, vegetable sticks, fruit, melamine plates and rainbow coloured cutlery. So when Tom sent around a photo of the day’s lost property, which included a distinctive fork of many colours, I put my hand up for it (responded with an emoji of an Asian woman raising a hand).

Tom has added you to the group: Fork/Off

Tom: You two have both claimed this fork

Martin: Happy to cede a fork

Tom: Martin I can’t believe you’ve just thrown in the tea towel

Me: Ooh that’s because I liked Martin’s forks so much I bought the same ones

[This is true. Martin’s partner hosted our book club for dinner, and she had lovely rainbow knives and forks. At the time we were unsuccessfully trying to get our girls to use cutlery instead of eating with their hands and I thought they might be just the thing…]

Tom: This is more like the film than I expected

Anyway, Tom suggested we meet up for a lunch/fork handover, since our offices are pretty close together, but he ended up seeing Elen first and giving it to her to give to me, but before she did, she took Lilian’s boys to the theatre and there was some kind of forkmergency which ended up with them taking it home and then giving it back to me. Sometimes things drift away but make their way back to you in the end.

Storms are hard to forecast until it’s too late. Where they will reach landfall; what the damage will be. And rebuilding after hurricanes is complex; I read an article recently about Brad Pitt’s attempt to build low-cost, sustainable houses for Hurricane Katrina survivors through his Make It Right foundation. The houses were designed by celebrity architects and used cutting-edge materials, but they weren’t suitable for New Orleans’ humidity and they basically collapsed, having grown mould and suffered the odd electrical fire.

When catching up with friends around our age, I’m aware of the need to tread carefully. You don’t always know where the no-go areas are, the sites of past disaster zones, structures at risk of collapse. It’s hard to avoid the subject of children, especially if mine are right there. And yet. Some of us have them, some of us don’t, some are childless by choice and others have gone through fertility treatments or are figuring out how to raise the topic of children with their online dates. And our families come in all sorts of permutations. Some of our friends are single parents, some have blended families, some are having their first children and others are having vasectomies.

I think it’s so important, as humans, that we can relate to people whose situations are different to ours, and have empathy for their situations. A recent chat brought back our experiences of infertility, something I don’t think about most of the time these days. I’ve written about our experiences with recurrent miscarriage before, but the part that stayed with me, that scarred my subconscious in ways I’m only realising now, is the part where I was told again and again that there was nothing to worry about. One miscarriage was perfectly normal and didn’t signify anything. That a second, shortly after, had no significance. When I had a third, a few months’ later, we had the standard tests that the NHS conducts under such circumstances, but they all came back normal, as they mostly do, except for one rather expensive genetic test, which they had requested for us anyway but isn’t super standard, and so they hadn’t noticed that the results weren’t there, but the odds of a previously undiscovered genetic problem were so low that we could dismiss that possibility. The doctor gave us an encouraging smile and told us to go off and have fun trying for a baby the old-fashioned way without worrying about what could go wrong.

Except after we’d left his office and were making our separate ways back to work, he phoned me and asked me to come back. He had chased up our genetic tests by phone. James’s was perfectly normal. Mine was not.

It happens in about one in ten thousand cases, apparently. At some point in the replication process, a piece of my genetic code went awry, splicing itself in the wrong place and displacing another piece of chromosome, which had to take the spot it vacated. It’s called a balanced reciprocal translocation, and it explains both why I’m so reassuringly normal (because it’s balanced, I have the right overall amount of genetic material, less any microdeletions/duplications which could have occurred) but also why half of my eggs aren’t. I’m not sure anyone knows exactly which chromosomes do what, especially the big chromosomes like the ones that are skewiff for me. But it means that at least half of my eggs have drastically the wrong amount of genetic material, and this condition could either lead to a baby with severe genetic abnormalities, or be incompatible with life (potentially more likely, given the three miscarriages I had already had). In addition to the background risk of miscarriage, this meant that every time I became pregnant, my odds of having a live birth were about 33%, and we had a higher risk of birth defects too.

I’d watched enough X-Men films to understand that genetic mutations could have pretty extreme effects. The genetic counsellor sent off a record of my particular mutation and medical history to a doctor in New York who is compiling a record of known translocations. I allowed myself to wonder if any of them had X-Men style effects, not like weather control or ice powers, but maybe something like expanded lung capacity and webbed feet which would make them unusually strong swimmers, or night vision, or perhaps a preternaturally strong sense of hearing. Apparently not, unfortunately. There were no records of anyone else with my exact mutation, but apparently people with unbalanced translocations that aren’t incompatible with life mostly have severe cancers rather than superpowers.

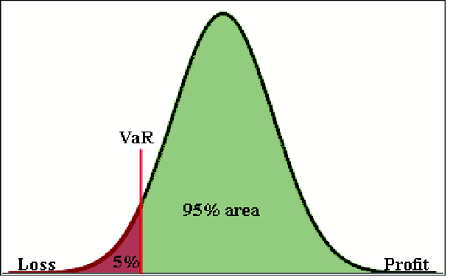

It was a hard set of outcomes to get our heads around. At the time, my job involved a lot of risk calculations. Risk is one of those concepts that it’s hard for all of us to make rational decisions around. We think about a catastrophic scenario, and its likelihood. There are names for risks: black swan events, which are so theoretically rare, that it’s not worth living your life trying to avoid them, because you can assume they won’t happen (until they do). Standard deviations indicate reasonably likely risks, the sort that make travel insurance worth paying for. Tail risks probably won’t get you, but would be devastating if they did, so you insure your house against fire. VaR is the value you lose for events at a certain likelihood, e.g. a standard financial risk measure VaR95 is your loss in a downside scenario that was 5% likely, i.e. a one-in-twenty event.

But it turned out I had a medical condition that is a one-in-ten thousand event, and my particular version was even rarer. I don’t blame the doctors for telling me not to worry. The other nine thousand, nine hundred and ninety-nine times, they’re right. Funnily enough, in a way that is not funny at all, the condition Theo had which required surgery this year, is just as rare. One in ten thousand babies is born with an issue like his.

The Butterfly Effect is a chaos theory concept based on ideas by the mathematician Edward Norton Lorenz, whose work focused on the importance of initial conditions in deterministic models and, appropriately enough, had a wide-ranging impact on many fields of mathematics.

It has been said that something as small as the flutter of a butterfly’s wing can ultimately cause a typhoon halfway around the world.

This isn’t really the same thing, it’s more the law of unintended consequences, or at least rich irony, but Lorenz’s mathematical cleverness indirectly led to one of the stupidest films of all time; The Butterfly Effect film stars Ashton Kutcher as an implausible genius blundering his way through the multiverse with ever more grotesque consequences. A horror show in every sense.

I’ve recently realised that my statistically unlikely misfortunes have had second order impacts as well. I’m a bit of a catastrophiser, even though I understand how annoying and pointless it is to constantly fixate on what-could-go-wrong. James is risk-averse in some ways, but will cheerfully enable other things like this, for example:

But for me it’s different. After months of being told that there was nothing wrong with me, and nothing wrong with Theo, it turned out that I was right to be worried. I should, in fact, have been more worried. There have been a few really notable things in our lives that have been breathtakingly shocking, that I didn’t see coming. But maybe I should have?

When you’ve been hit by typhoons enough times, you start to worry about every butterfly wingbeat. What chain of events is being set in motion which is going to bring something heavy down on our heads? There are butterflies everywhere, and you don’t know which of the little winged bastards is about to blow up your life.

And of course I feel guilty about thinking any of this. I should buck my ideas up. Check my privilege. What right do I have to feel sorry for myself, really? We were blessed with children in the end. Theo’s receiving amazing care and has a good chance of a normal life. Other things which have happened, we’ve endured. The things that are currently keeping me up at night are nothing compared to the worse things happening right now in conflict zones and under totalitarian regimes and to ordinary people behind closed doors.

The morning before the picnic, the day of the storm, I went with my friend The Bookish Persian's Substack to an exhibition of Persian rugs at Union Chapel, the private collection of a family who were offering them for sale. It was the perfect setting; vaulted ceilings and dark wood panelling, red velvet curtains and a fantasy of woven dreams spread underfoot. We trod carefully over beasts and flora and geometric patterns in rich colours and gorgeous textures, dense wool and shining silk. The family laid on an incredible spread of Persian food as well; fragrant tea and smoky aubergine dip, fresh bread and chicken Salad Oliveri. It was spectacular. But when we got talking to the daughter of the family, she explained that the rugs had belonged to her grandparents, who had recently fled Iran, and to her father, who had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and wanted to bring the family’s rug collection down to more manageable levels. He had come up with the idea of the sale and exhibition, and even made all the food.

It was humbling. He has taken real suffering and used his resources and skills to create something meaningful and beautiful. Me? My response to having a tough time has been to go to bed early and cry a lot.

“I'm really sorry,” I said to the work-provided counsellor on the phone. “You've probably got loads of people having worse times than me. I shouldn't be taking up your time. I should be more resilient to all of this stuff*.”

(*an incomplete list of “this stuff” can be found in previous editions of this newsletter comprising bereavements, Theo's surgery and hospital stays, but there's also been a cacophony of background noise that has sometimes become foreground noise from my day job, my side gig and the gradual crushing of some other dreams, along with close family and friends going through illnesses, marriage breakdowns, job losses and mental health struggles).

“What do you find helpful?” the counsellor asked. Wonderfully, this list came to mind just as easily. My supportive and stoic spouse and our shared faith in God. Emotional and practical support from family and church family, accommodation from work. Natural endorphins from low-key exercise three times a week, breathing exercises, praying and reading the Bible, escaping into novels (I've read over a hundred books this year so far, and review most of them on Instagram), catching up with friends, hugs with my children. We picked out some favourite picture books to celebrate World Mental Health Day and I realised that one of them depicted the counsellor’s suggestion of worry journalling:

In THE WORRY MONSTERS by Sue Lancaster and illustrated by Kevin Payne, three children imagine that their worries are personified as monsters. They visualise the monsters’ appearances and identify what their worries are: fear of the dark, anxiety about going to school, stage fright. But instead of trying to drive the monsters away, or trap them where they are, they approach them gently and with compassion, reassuring them until they eventually flutter away, like butterflies. The kind that might cause large-scale natural disasters and widespread devastation, but then again, they might not.